How Does Money Get A Face?

Why Abraham Lincoln? Ok fine, that one seems obvious. But William McKinley, Chief Onepapa and Martha Washington? How did their famous faces end up on our currency, if only for a brief moment?

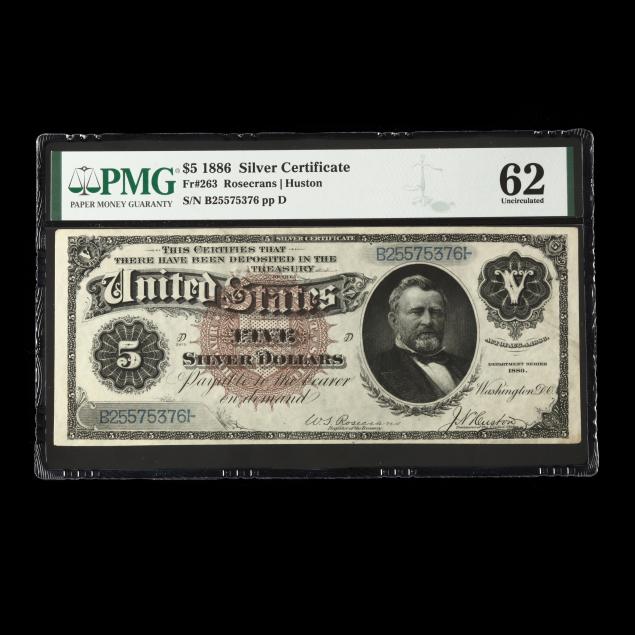

Ulysses S. Grant currently graces the $50, but as a Series 1886 $5 Silver Certificate note in our Rare Coins session proves, that was not always the case. Where does the buck stop for deciding who goes on which bill or coin?

The answer is, as with most things bureaucratic, not a simple one. These days theoretically the Secretary of the Treasury has the final say, but Congress can and sometimes does act to put a new face on a bill or coin. To wit, current plans to feature suffragettes on the reverse of the $10, replacing Andrew Jackson with Harriet Tubman on the $20, and several recent stirrings in Congress to replace Grant on the $50 with Ronald Reagan (which have been vehemently resisted by representatives from Grant's home state of Ohio).

One thing is certain: it is illegal to put any living person on United States currency. George Washington set the precedent when he declined to have his face on the very first US Mint coins, breaking with the global tradition of having current monarchs and other rulers on money. But it didn't actually become illegal to put a living person on American money until just after the Civil War, when Congress passed an act making it so.

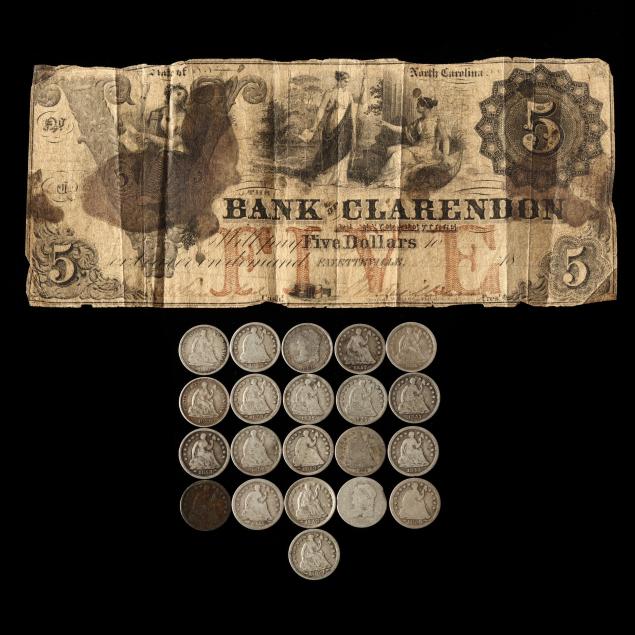

Interestingly, it was only during the Civil War that the United States began issuing its own legal paper money (notes printed prior to the Legal Tender Act of 1862 were issued only by private banks). "Greenbacks" as the new paper notes were known, were one of the lasting devices, along with a national bank and the agency that would become the IRS, that Salmon P. Chase, Lincoln's Treasury Secretary, put in place to pull the Union through the massively expensive Civil War. He was a smart man, and he knew it. And to make sure everyone else knew it he put his own face on the first national mint-issued dollar bill. The story goes that since he put Lincoln on the $10, he felt he was being sufficiently modest by only claiming the $1.

And so it was perhaps in reaction to Chase's self-aggrandizement that Congress passed the 1866 act to prohibit likenesses of the living on our money. There have been several exceptions over the years - Calvin Coolidge was on the 1926 half dollar commemorating the Sesquicentennial of American Independence; Eunice Shriver made it on to the obverse of the 1995 Special Olympics World Games Commemorative Silver Dollar; several now-obscure Senators graced coins commemorating their respective states.

The answer is, as with most things bureaucratic, not a simple one. These days theoretically the Secretary of the Treasury has the final say, but Congress can and sometimes does act to put a new face on a bill or coin. To wit, current plans to feature suffragettes on the reverse of the $10, replacing Andrew Jackson with Harriet Tubman on the $20, and several recent stirrings in Congress to replace Grant on the $50 with Ronald Reagan (which have been vehemently resisted by representatives from Grant's home state of Ohio).

One thing is certain: it is illegal to put any living person on United States currency. George Washington set the precedent when he declined to have his face on the very first US Mint coins, breaking with the global tradition of having current monarchs and other rulers on money. But it didn't actually become illegal to put a living person on American money until just after the Civil War, when Congress passed an act making it so.

Interestingly, it was only during the Civil War that the United States began issuing its own legal paper money (notes printed prior to the Legal Tender Act of 1862 were issued only by private banks). "Greenbacks" as the new paper notes were known, were one of the lasting devices, along with a national bank and the agency that would become the IRS, that Salmon P. Chase, Lincoln's Treasury Secretary, put in place to pull the Union through the massively expensive Civil War. He was a smart man, and he knew it. And to make sure everyone else knew it he put his own face on the first national mint-issued dollar bill. The story goes that since he put Lincoln on the $10, he felt he was being sufficiently modest by only claiming the $1.

And so it was perhaps in reaction to Chase's self-aggrandizement that Congress passed the 1866 act to prohibit likenesses of the living on our money. There have been several exceptions over the years - Calvin Coolidge was on the 1926 half dollar commemorating the Sesquicentennial of American Independence; Eunice Shriver made it on to the obverse of the 1995 Special Olympics World Games Commemorative Silver Dollar; several now-obscure Senators graced coins commemorating their respective states.

But for the most part, the standard holds. A president must have been dead for two years to be included in the Presidential $1 coin series, less for other money. Within a month of John F. Kennedy's assassination plans were in the works to remember him on one of the larger silver coins. It's said that Jacqueline Kennedy opted for him to replace Benjamin Franklin on the half dollar rather than taking Washington off the quarter.

Thirty-Four (34) 1964 90% Silver Kennedy Half Dollars

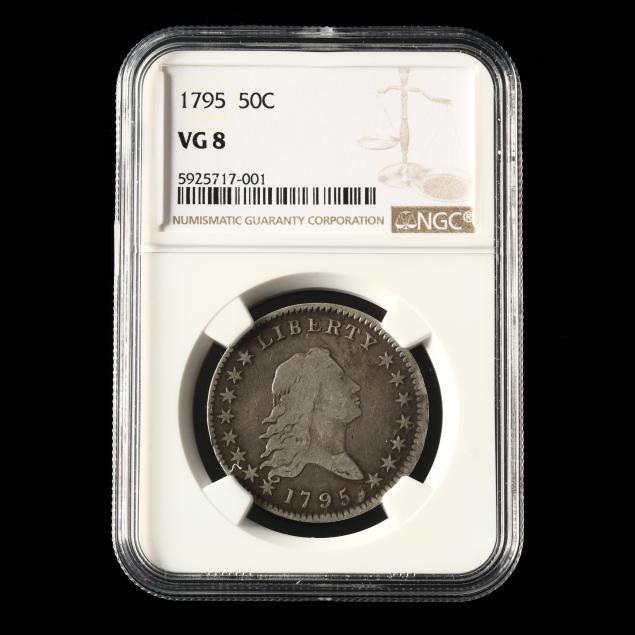

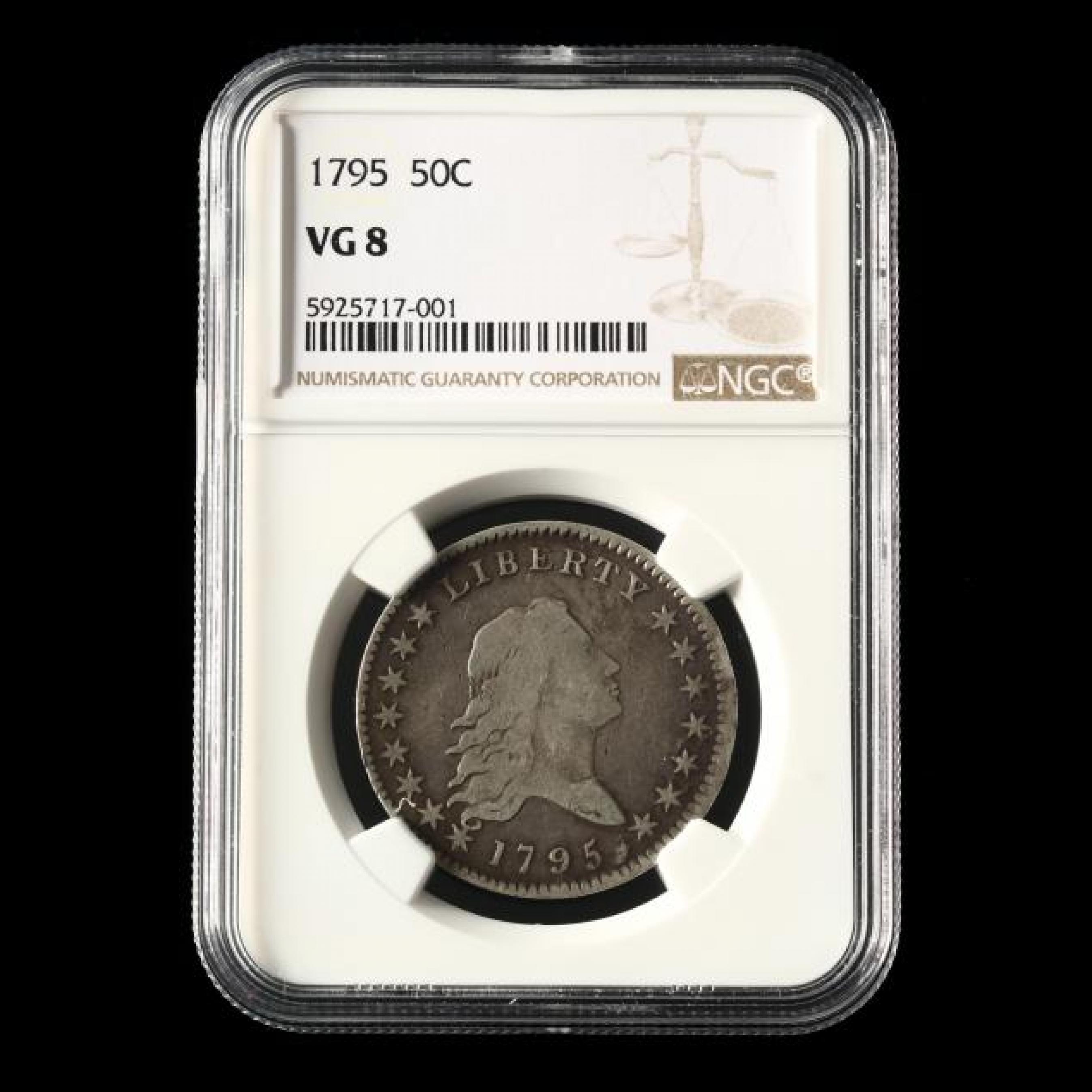

A 1795 Flowing Hair Half Dollar, NGC VG8, in the Rare Coins Session

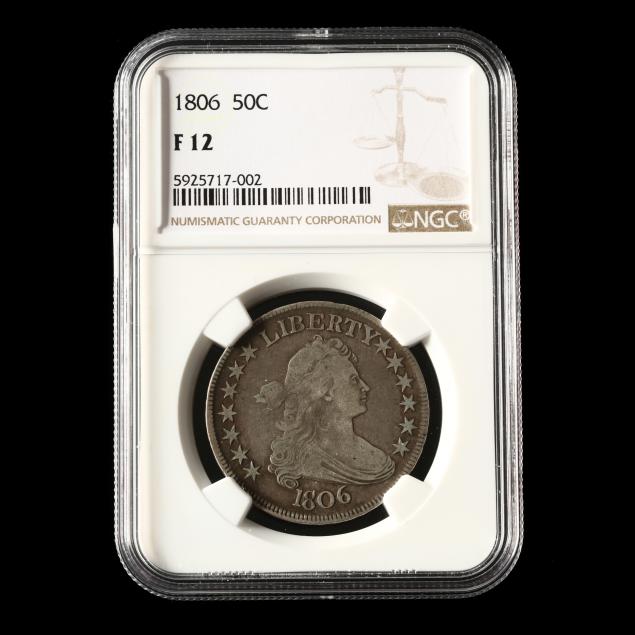

While living people aren't allowed to appear as themselves on money in the United States, they have been able to stand in as other characters. After George Washington declined to have his face on the new United States' currency, Lady Liberty took his place and has turned up on our coins in all manner of poses, hairstyles, dress and undress. But while the Lady herself may be an allegory, her face is decidedly human. Over the centuries she has been based on an ever-changing cast of engraving artist's wives and muses.

As the depiction of an ideal, there is surely much to be read into Lady Liberty's evolving looks. In recent years she has had a much more diverse countenance, and future plans are that she will not have one face, but many, to more accurately reflect the female population of our country. As Leland Little Coin Director Rob Golan helpfully reminds us, the value in old coins and bills lies as much in their historical relevance as their monetary equivalence. They can tell us so much about what, and who, was important to the people who used them as currency.

Estate Jewelry, Rare Coins, & Sterling Silver

Featured Lots

Thursday, February 11th

10:00am

Estate Jewelry, Rare Coins, & Sterling Silver

Featured Lots

Thursday, February 11th

10:00am