The late Betsy J. Sykes, as her companion in travel and collecting Ted Gosset remembers her, was Southern house proud with a New England sensibility. Mrs. Sykes kept a beautiful home and garden as any good Southern hostess would, but she preferred to curate her surroundings with the simplicity of a Northerner. Delftware, both Dutch and English, was hugely popular with early colonial Americans in New England, and its broadly beautiful designs fit perfectly in that Northeastern aesthetic that finds graciousness in restraint. Mrs. Sykes's wonderfully diverse collection of Delftware is being offered in the sale of her estate.

The history of Delftware is itself the story of applying a practical bent to the decorative arts. The Dutch pottery industry was in full swing by the beginning of the 17th century, and Dutch potters had learned methods for using a stanniferous (tin) glaze from trade with Italy and Spain. When the Dutch East India Company began to import Chinese porcelains, which were mystifyingly thin and rendered in crisp blues and whites, Dutch potters found that their tin glaze was the perfect base layer to help mimic the newly popular delicate eastern porcelains with their coarse European clay.

When the Sino-Dutch wars broke out in the mid-17th century, over trading rights in the Pacific and at Chinese ports, Dutch traders' access to their lucrative shipments of Chinese porcelain was curtailed. The potters of Delft were poised to handle the European demand. The canals of Delft, once a source of clean water for the plentiful local breweries, had become too polluted to use for beer, so the deserted breweries that lined them were converted to pottery factories - potters need water too, and it didn't matter to the pottery if the water was especially clean.

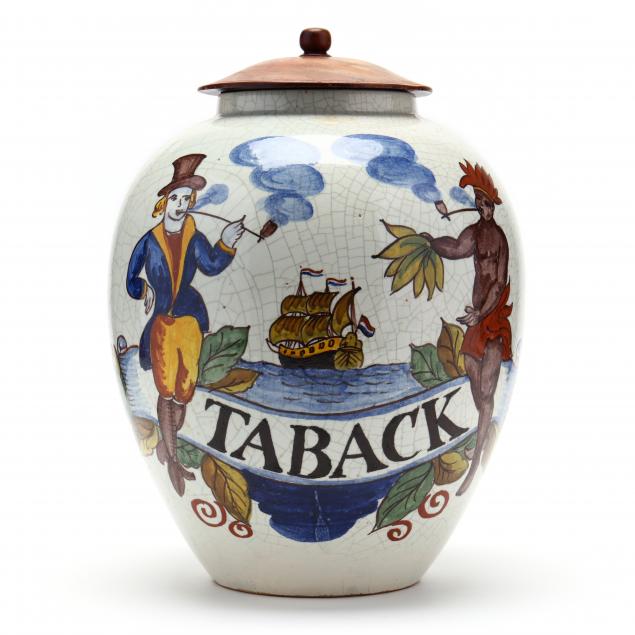

At first Dutch potters exclusively copied the Chinese blue and white designs. But as production of Delftware flourished, they began to incorporate motifs that related to their own lives and lore. And, once the Dutch discovered Japanese Imari porcelain, with its richly polychromatic designs, they too saw fit to add colors beyond the basic blue and white to their work. Interestingly, when trade re-opened between the Netherlands and China, the Dutch began to export Delftware back to the East, and Eastern porcelain-makers copied the newly Dutch-ified designs in their own work, to sell back to Europe. The trade circle was complete, several times over.

In 1677, Queen Mary II of England married William of Orange from the Netherlands. Upon visiting her husband's home country, she fell in love with Delftware, making it the new requisite accessory in noble homes in England. Like the Dutch had before them, English artisans made what the market demanded, creating English "Delftware." Eventually, both the Dutch and the English began to transport their wares across yet another ocean to sell them to their colonies in the New World. A Northeastern American decorative style was born that fit perfectly with simple wood furniture and a Protestant sensibility.

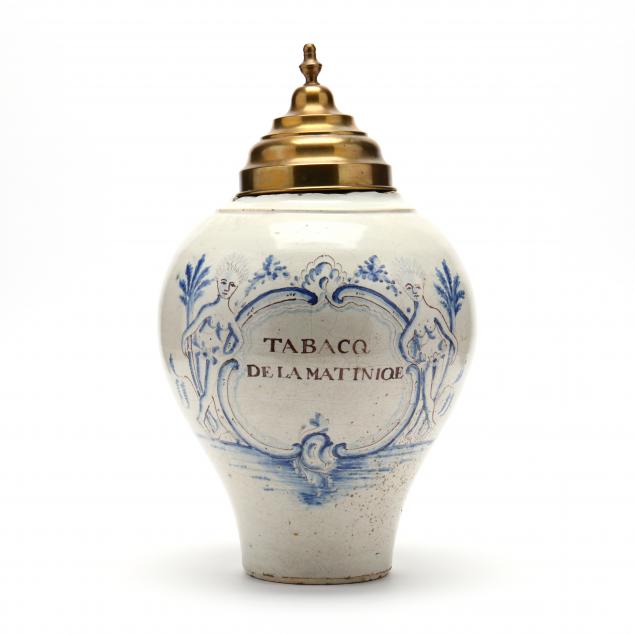

Mrs. Sykes's collection of Delftware incorporates pieces from both the Netherlands and England, as well as French "faience" porcelain, a technique developed later to make thinner wares that more closely resembled their Eastern inspiration. Through the Sykes collection it is possible to trace the whole journey of Delftware, from European opportunistic artisanry to an American collector's prize. Art and commerce are not always comfortable bedfellows, but in the case of Delftware, they are inextricable.